Getting started with Aligned Incentives, the gift card reseller-cum-bill broker

/When I write about gift card reselling, I usually give the rates available on the cards available for sale to CardCash.com. I do not and have never had any financial relationship with CardCash except that they buy my gift cards, let alone an affiliate relationship, but I use them as a reference for two simple reasons.

First, they are still in operation, unlike a lot of gift card resellers that have come and gone over the years.

The Plastic Merchant was one of the more notorious, if not the biggest, gift card reselling collapses because so many online travel hackers were personally affected and wrote about the resulting bloodshed.

Other long-established sites haven’t folded entirely, but have pivoted to other models. Gift Card Granny no longer buys gift cards, and is now just a skinned version of traditional gift card websites. Raise spun their gift card reselling “marketplace” into GCX, which sounds like it is narrowly targeted at people putting extremely high volume through the platform.

The second reason I use CardCash when citing gift card resale prices is that you can check their prices in real time without logging into the website or having an account. This may not sound like much, but I strongly feel that when you write for a public audience then the public should be able to easily check your work, both because it allows errors to be spotted more quickly and because I’m not interested in troubleshooting every reader’s attempts to sign up for every service I mention.

Citing a public website that works on mobile browsers solves both problems, so I cite CardCash.

Getting started with Aligned Incentives

Having said that, a number of readers reached out to encourage me to get up to speed on Aligned Incentives, for a number of very convincing reasons. Most importantly, CardCash doesn’t provide public quotes for Amazon gift cards. Aligned Incentives requires an account, but buys those gift cards at a “base” rate of 91-93.5% of face value (depending on denomination), which makes it one of the most lucrative possible ways to liquidate frequently-bonused “Zift” gift cards at grocery stores.

More about “base” purchase rates in a moment.

Aligned Incentives is open to new users, although they do require you to use Google credentials to set up your account. Their new user guide is also available to the public. It’s not great literature, but I strongly encourage you to read it start-to-finish to understand the kind of company you’ll be dealing with if you decide to proceed.

Notification settings

The very first thing you will notice after creating an account is the sudden onslaught of e-mails. This will become unbearable immediately, so you will start trying to figure out how to turn them off.

Achieve this by clicking on “Notifications” in the bottom left of the main screen:

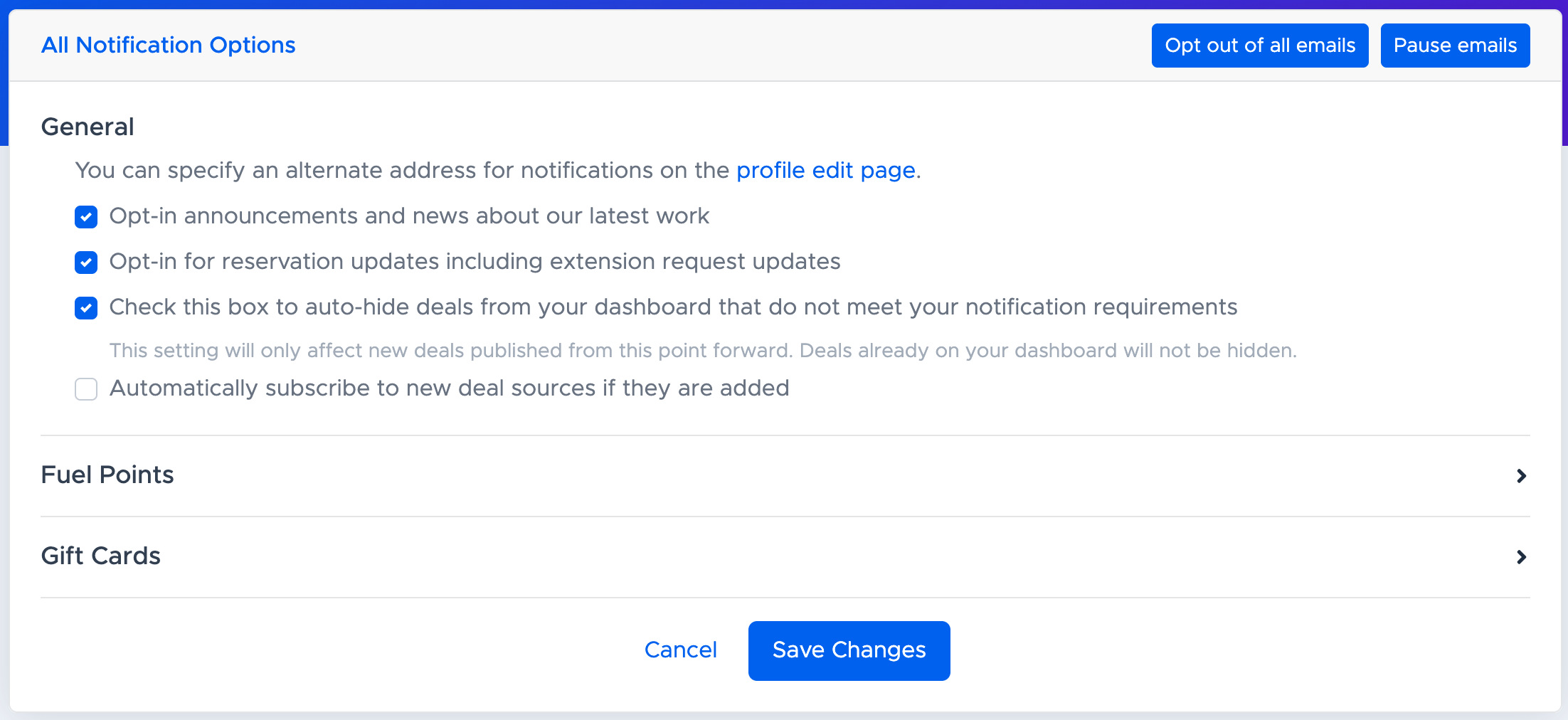

Then “Opt out of all emails:”

This will shut off the stream of e-mail notifications for the time being.

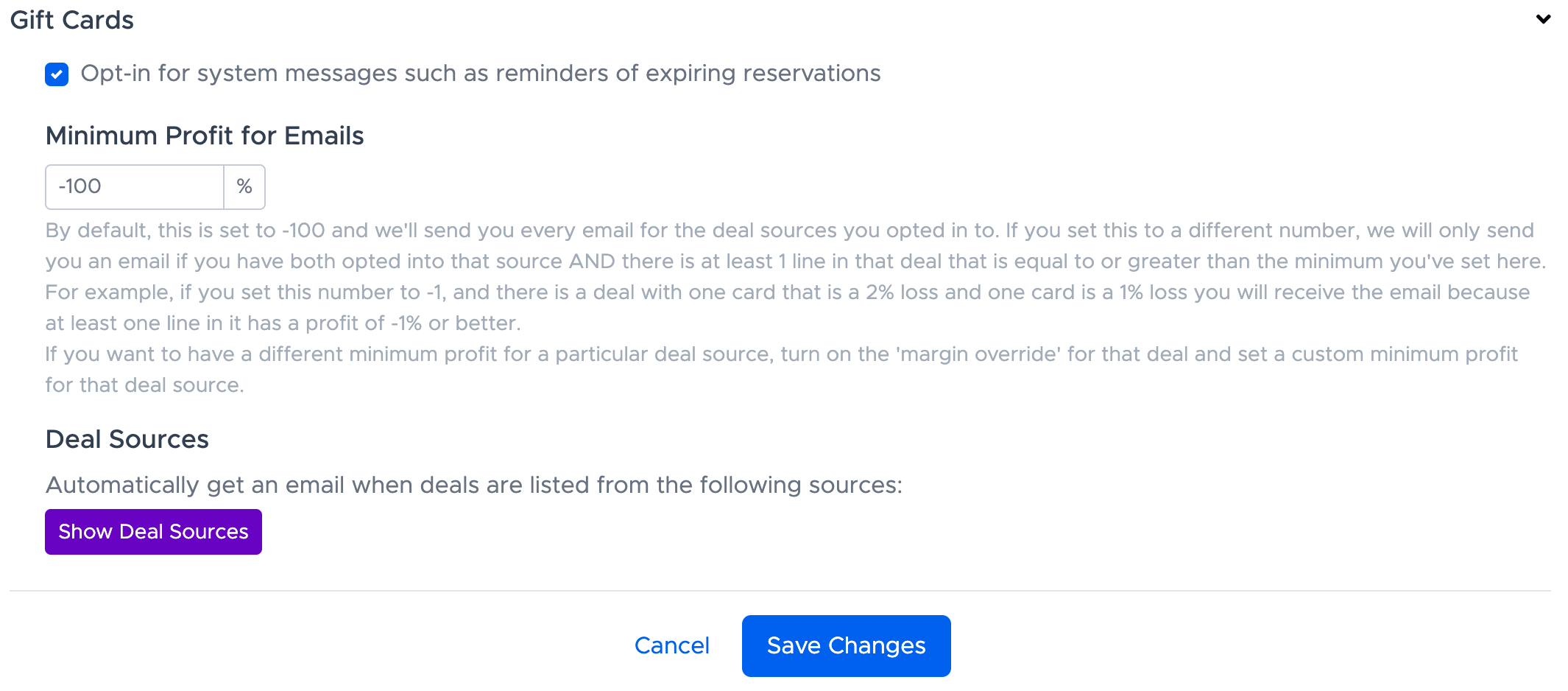

Next, it’s time to decide what deals you actually are interested in. Expand the “Gift Cards” menu and click “Show Deal Sources,” in purple:

Here you’ll find a list of every merchant Aligned Incentives has ever issued a deal alert for, plus the all-important “Anywhere,” which is how deals are listed when they’re offering to buy gift cards without being attached to any particular deal. After unselecting all (and adding back “Anywhere,”) you should now look over this list to see which merchants apply to you.

I live in a city with both Safeway and Giant grocery stores, but without Kroger or H-E-B stores. Kroger and H-E-B may offer great deals, but I don’t want to get e-mails about them. If you live in Texas your situation might be the exact opposite!

Notifications settings will inform your dashboard

Once you’ve got your notifications set up properly, the third checkbox on the Notifications page starts doing its work: “Check this box to auto-hide deals from your dashboard that do not meet your notification requirements.” With this box checked, after a week or two (when older deals have had a chance to fall off) your “Seller Dashboard” should more or less reflect the deals that are relevant to you.

Selling gift cards

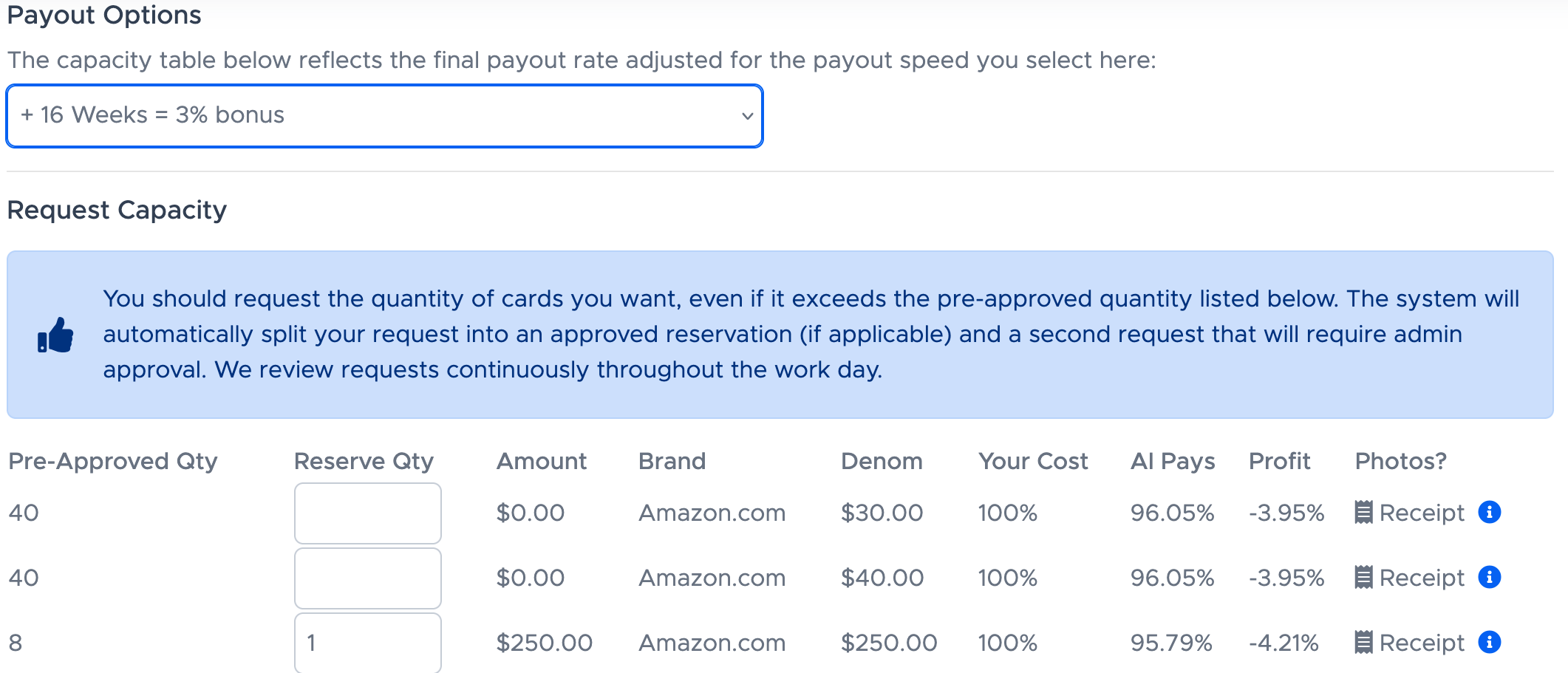

At this point, Aligned Incentives mostly works like a normal gift card reselling site, with a few nuances. First, before you submit gift cards for sale you have to “reserve” specific numbers of cards in specific denominations.

The price and volume for different denominations will be different, but fortunately most merchant gift cards don’t have purchase fees so you should be able to purchase cards in the most lucrative denominations — as long as the clerks at your local stores are willing to go along, of course.

Second, when you’re ready to submit your gift card numbers, Aligned Incentives also requires you to upload a receipt showing you purchased the cards with a credit card. This was a major source of confusion for me at first, but as I understand it they are only trying to ensure that people aren’t laundering money by purchasing gift cards with cash. They’re not verifying the actual credentials of the card you purchased.

Upon even a moment’s reflection this seems absurd: a mobster could simply give someone with a credit card the cash they wanted to launder, and the cardholder could give the gift card and the credit card receipt to the mobster. But criminals are as lazy as everybody else, so maybe adding the trivial friction of the extra step keeps the very laziest of them off the streets.

Payout timing and Aligned Incentives’ shadow banking function

The timing of gift card reselling payouts is the essence of the business: the longer the payout timeline, the longer your money is exposed to the risk of default (as illustrated most pitifully in the case of The Plastic Merchant mentioned above).

CardCash approves my submissions within one or two business days and I receive my payments within a business day or two after that, which gives a payment timeline of between 3 and 6 calendar days: a card submitted on Friday before a long weekend might not be approved until the following Tuesday, with the payment ultimately received on Wednesday or Thursday, but a submission on a working Monday is almost certainly going to be paid out by Thursday or Friday at the latest.

Aligned Incentives has a “standard” payout timeline of 2 calendar weeks from the time your gift card is submitted. Adding a business day for the ACH payment to be received, and the possibility of intervening weekends and Monday holidays, this gives a payment timeline of 15-18 calendar days.

But here Aligned Incentives introduces a secret second function: that of bill broker. This is an industry now associated (if it’s associated at all) with the history of London’s Lombard Street due to Walter Bagehot’s brilliant essay on the industry, but continues after various transfigurations to this day. A common example is freelance and platform workers, who are often offered versions of a deal where their employer offers to pay 100% of their agreed earnings in 6, 8, or 12 weeks or 95% of their pay today.

As exploitative as these employment arrangements are, they only magnify the basic logic that when you are only paid once or twice a month, you are lending your labor to your employer interest-free on the faith that they’ll have the money to pay you when your bill comes due. The sooner you’re paid, the less faith you need to place in your employer: day laborers need only a day’s worth of faith that the money will be there, and the next day are free to place their faith in another employer, perhaps with a better reputation for on-time payment.

It is generally illegal in the United States for non-banking institutions to take interest-bearing deposits. But Aligned Incentives developed a clever workaround: instead of accepting deposits and paying interest on them, they “purchase” merchandise (your gift cards) and pay higher rates for delayed payments. This is the essence of bill brokering, or what is now called “factoring” and in one of its even more esoteric forms “reverse factoring.”

Gift card sales are deposits into Aligned Incentives high-interest-rate ecosystem

What Aligned Incentives really offers is unsecured deposits into its high-interest-rate bill brokerage ecosystem. Allow me to illustrate this with a current deal.

Mid-Atlantic Giant/Stop&Shop/Martin’s grocery stores are currently awarding 8 points per dollar spent on Zift gift cards (worth 8% in grocery rewards or 8 cents per gallon at participating partner gas stations). Several Zift versions offer Amazon.com gift cards as one of many possible redemptions.

If you purchase a $250 Zift gift card, using a credit card that offers 3% in rewards, the purchase itself will generate a minimum of $27.50 in total rewards, meaning what an investor would call their “cost basis,” the amount they’re actually out-of-pocket, is down to $222.50. After converting it into an Amazon gift card, it’s worth $232.50 to Aligned Incentives in 15-18 calendar days, and you can profit $10 for your trouble.

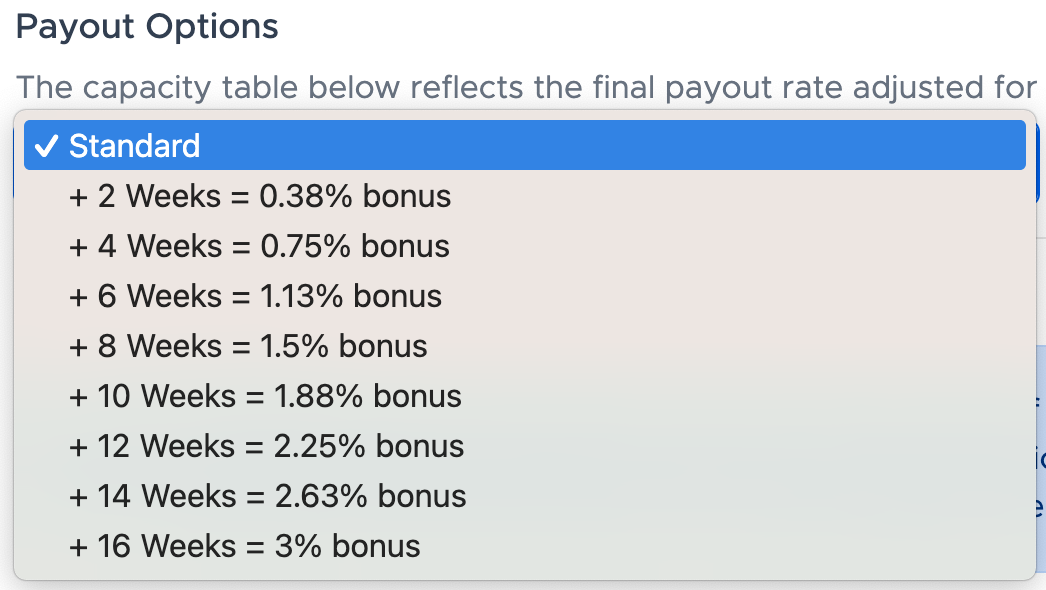

But here Aligned Incentives offers the same deal it would otherwise be illegal for an unregulated financial institution to offer: consider your payment, which you’re entitled to in 15-18 days, as a deposit, and they’ll pay you up to 3% more if you’re willing to wait up to an additional 16 weeks (127-130 days total):

Here the same $250 Amazon gift card, purchased for the same $222.50 after rewards, is worth $239.47, a 3% cash return for leaving your $232.50 on deposit with Aligned Incentives for an additional 16 weeks.

The advantages of an an almost completely flat yield curve

I want to make one final point before concluding. A yield “curve” gets its name from the observation that most investors demand a higher interest rate on longer-term debt obligations than shorter-term ones, both because over longer periods repayment becomes more doubtful and because locking in a long-term interest rate means you’re not able to invest the same money if rates should rise before your first investment matures.

But Aligned Incentives doesn’t use that model. The interest rate they pay on delayed payments is essentially flat across the entire repayment structure:

I only say “essentially” flat because the first two (interest-free) weeks are more significant to the interest calculation the shorter the total repayment period is. The proof of this is left as an exercise for the reader.

Conclusion

To come full circle, I do not believe Aligned Incentives is an especially well-capitalized debtor that is especially likely to full its debt obligations, any more than I thought The Plastic Merchant was an especially well-run organization before they defaulted on theirs.

What I do believe is that if you are already floating debt to Aligned Incentives for payment in two weeks, you’re already taking a credit risk on their ability to fulfill their obligation. If you understand that, then you are ready to decide whether you’re willing to float the same debt for 2-16 weeks longer, with the opportunity of earning elevated returns while your money is on deposit.

“Platform risk” is the most important risk any travel hacker takes, and you should not delude yourself that gift card reselling is any exception. If Aligned Incentives goes under there’s no chance you’ll ever receive your payments, whether you made your deposit one or 126 days ago.

But if you’re willing to risk money on deposit to the platform, then they currently offer a generous annualized rate of return on those same deposits.